This blog posting is more than twice the usual length, to keep the information on this infrequently visited area within a single entry.

After finishing up our “Southeast” agenda, which took about six months, there were no firm plans for the remainder of the year. Cooler weather, more remote camping, and paddling opportunities sounded good, so we decided to visit an area new to us in eastern Canada. Between re-provisioning, research, repairing and replacing gear, and addressing minor medical issues, we had much less time for visiting in the northeast U.S. than was the case last fall, but we did manage to see a few people along the way, and appreciated our friends Allan and Andrea hosting us in their driveway while we got things sorted out.

We have previously driven nearly all the great roads in arctic Canada and Alaska, including the Haul Road to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska; the Dempster Highway in the Yukon; the Alcan Highway; Route 3 to Yellowknife, Northwest Territories; and the Trans-Labrador Highway. But there was one little-known omission on our list, a series of roads east of James Bay, in Quebec. Though these roads do not reach true tundra habitat, and do not go nearly as far north as some of the roads mentioned above, they do provide access to boreal habitats with an interesting collection of species, and are quite an adventure to travel.

After crossing the Canadian border near Watertown, New York, we camped near Thousand Islands National Park, which we had not visited before. We paddled there the next day, out to islands in the Saint Lawrence River. Although the forecast was OK, a localized but serious storm snuck up between us and the mainland, and we were fortunate to reach an island shelter just moments before all hell broke loose. Even the swallows flying over the river came in to roost in trees to wait out the wind. It was all over less than an hour later and we had a nice paddle back. We camped the next night in Reserve Faunique La Verendrye, a fine canoeing destination in Quebec, where in 2005 we saw a Pine Marten. We had a lovely 8-mile paddle there, on which we photographed three species of odonates (dragonflies and damselflies) that we had not seen before. The next day, July 30, we reached Matagami, 450 road miles northwest of Montreal, and the starting point of our James Bay adventure.

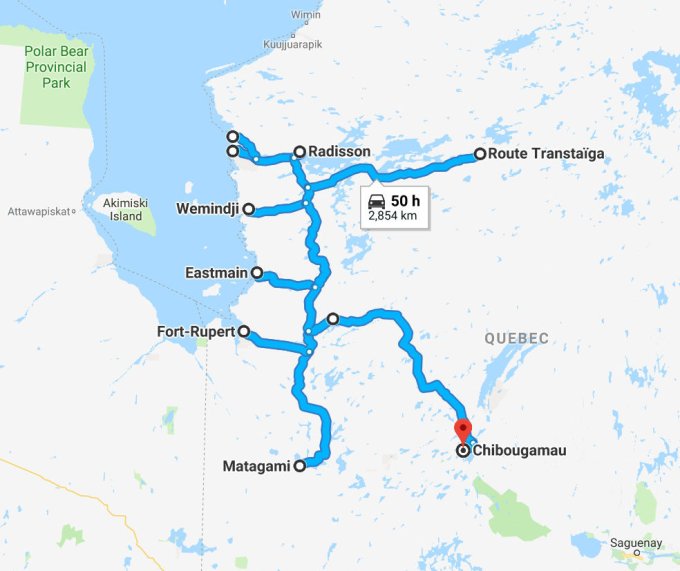

The map below shows our route from Matagami (population 1500) to Chibougamau (population 7500). The widening from large James Bay (about 250 by 100 miles) to the southern end of enormous Hudson Bay (about 700 by 600 miles) is visible in the top left corner of the map. This region is sparsely populated; there are just five Cree villages with a total of about 10,000 people, and Radisson, a settlement supporting Hydro Quebec operations, with a few hundred people. In 19 days we drove 2000 miles, 1100 miles of which were on gravel roads. The main north-south road is the James Bay Road, hereafter “RBJ” from the French name, Route de la Baie-James. From south to north, the roads going west from the RBJ to James Bay lead to the Cree villages of Waskaganish, Eastmain, Wemindji, and Chisasibi; a side road going northwest from the latter reaches uninhabited Longue Pointe on James Bay. The more northerly road going east from the James Bay Road is the Trans-Taiga Road (Route Transtaiga in French), built to support hydroelectric facilities. The more southerly road going east from James Bay Road is the North Road (Route du Nord), which ends near Chibougamau.

As required because of the remoteness of the region, we registered at the visitor station at Kilometer 6 (Km6) of the RBJ, where we obtained some helpful information regarding location of camping areas and gasoline. The first day we made it as far as the “rustic campground” at Km80. There are 14 such campgrounds on the RBJ; they typically have five to ten small sites with picnic tables, an outhouse, and a dumpster, but no running water or other utilities. The campgrounds have a suggested donation of $5 per night and some, especially farther north, are very nice; many have boat ramps to pretty lakes.

The boreal forests we saw were dominated by Jack Pine (Pinus banksiana), White Spruce (Picea glauca), Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides), Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera), and, in wetter areas, by Black Spruce (Picea mariana), Tamarack (Larix laricina), and Green Alder (Alnus viridis). Highlights of the day were sensational displays of flowering, magenta-colored Fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium), Sandhill Cranes in breeding habitat, and a new bulrush (Scirpus georgianus), which was common. Biting insects were a problem in the campground, with swarms of blackflies, deerflies, and, at dusk, mosquitoes. On the second day we made it to camp at RBJ Km232. We were a bit surprised to find Common Nighthawks this far north, but in fact continued to see them for most of the trip. We found the tiny Downy Rattlesnake Plantain orchid (Goodyera repens) for only our third time ever, and added two butterflies, Arctic Fritillary and Dorcas Copper, to our life list.

On our third day we left the RBJ to visit Waskaganish (accent on the second syllable), our first Cree village. Virtually all Cree speak English fluently, and their villages have a good assortment of supplies and services, as well as cell signal. Both to improve chances of spotting wildlife, and decrease the chances of flat tires, we drove the 65-mile gravel road to Waskaganish (and all subsequent gravel roads) at the sedate pace of 25 mph. (Based on experiencing scores of flat tires in my travels, I have come to believe that all else being equal, the probability of a flat tire per unit distance increases exponentially with velocity, with a doubling every 15 mph or so.) Soon after leaving the RBJ on any of the westward roads, the land changes from Category 3 — crown land, on which dispersed camping is permitted — to Category 2 or 1 — native lands where permission is required to camp. Permission can be obtained by contacting the Tourism Officer in the village, which we did in Waskaganish, where we kindly were permitted to stay on a bluff above rushing rapids of the Rupert River. The nearby muskeg (wet, grassy habitat with scattered small shrubs and trees) had a marvelous collection of boreal plants, including the largest populations we have ever seen of the unique monocot Pod-Grass (Scheuchzeria palustris). This species, placed in a family by itself, is found in both the New and Old Worlds, a not uncommon occurrence among far northern plants. Other botanical highlights were a tiny twayblade orchid (Liparis loesselii) in fruit, and a tofieldia (Triantha glutinosa). We also began finding more northerly species of birds such as Spruce Grouse, Gray Jay, and Orange-crowned Warbler.

In the morning we met with the tourism officer, Tim Whiskeychan, a famous artist, and learned a bit about the Cree. They were celebrating the 350th anniversary (!) of their contact with Caucasians, from the Hudson’s Bay Company, though they had occupied areas around James Bay for far longer than that. Next, we paddled downstream on the Rupert River to James Bay proper, although some maps show the coastal indentation here as Rupert Bay, a bay off James Bay, itself a bay off Hudson Bay! Paddling here is tricky because the tides are so great – there was about a 25-foot difference between low and high tide when we were there! This means that if you enter an area of shallow water on a falling tide, the water can suddenly retreat faster than you can paddle, leaving you stranded in mud until the tide rises again. Once on the shore of James Bay we began seeing a different, more arctic assortment of plants, and all eight plant species we added to our life list during the rest of the trip, were within sight of the James Bay shoreline. We finished the day by waiting until dark, and then slowly driving the road back to the RBJ to look for mammals. We did not see a single thing, not being helped by a light but steady rain, and we finally reached camp around 1:00 a.m.

We spent the next day in camp at RBJ Km 257, recovering and catching up on plant identifications. There were some nice multi-species flocks of migrating songbirds moving through. The next day was another very long one, traveling the road to the Cree village of Eastmain, a contraction of the Hudson Bay Company designation of “East Shore of James Bay, Mainland”. We arrived at just the right time to paddle out to James Bay on the Eastmain River. With high tide about two hours away, we could paddle for two hours and return by the same route, knowing that at each point the water depth would be about the same when we returned as when we went out, reducing the chances of becoming stranded. Most of the islands in Hudson and James Bay belong to the territory of Nunavut, which was separated from the Northwest Territories in 1999. We were actually able to make landfall on one of these islands, a neat way of reaching this very remote territory! We had been in Nunavut only once before, in 2000, visiting Baffin and Bylot Islands. In 45 minutes on the island, we found four new plant species, one belonging to a genus we had not seen before (Honckenya peploides, Seaside Sandplant)! We finished just in time for a late dinner and another slow drive at night for mammals. Despite using our thermal scope mounted outside the truck, to increase the chances of detecting mammals, we again had no luck.

After another 1:00 a.m. arrival at camp, at RBJ Km 323 (Mirabelli Lake, the best campsite of the whole trip), we again took a day off to recover and key plants. Eileen took her morning coffee behind the site, where she had a fine view of some muskeg. Something caught her eye and when she turned her head, there was a beautiful Pine Marten (Sable) just ten feet away! It spent a few minutes considering whether it was safe to pass, climbing a small tree to eye level to get a better look at Eileen. The marten decided it was OK and continued on right in front of her, completing a fantastic experience!

On the next day, at RBJ Km428, Eileen spotted a wolf, a beautiful animal that we saw quite well! Wolf taxonomy is controversial, but in brief, the animal we saw could have been either the widespread Timber Wolf (Canis lupus), or a population often regarded as a separate species, the Eastern Wolf (C. lycaon), which is very closely related to the Red Wolf (C. rufus) of the southeastern U.S. (considered extinct in the wild by 1980). Some published range maps show Eastern Wolf east of James Bay, others shown Timber Wolf there, and they are not easily distinguished by appearance, though our animal was quite rufescent, favoring Eastern Wolf. We also saw one other wolf later in the trip, at the end of the RBJ.

Continuing to Wemindji, we obtained permission to camp overnight in town, on the bank of the Maquatua River, so we could paddle it the next day. It was a little too windy to go out on James Bay, where we could have visited other islands in Nunavut, but there were lots of more sheltered waters to explore, and we found two new plants at our lunch spot. This was followed with yet another long night-time drive using the thermal scope, on which we saw our first Snowshoe Hare of the trip. We camped at RBJ Km574 and stayed two nights, once again allowing for some recovery time, as well as a chance to work on blog posts.

The second evening we were totally inundated with mosquitoes at dusk. They found their way in through small gaps, and it took twenty minutes with a lithium battery-powered hand vacuum to mostly clear the camper of them. Mosquitoes detect carbon dioxide exhaled by animals, and we hypothesized that they were homing in on air leaking out of the camper at junctions of seals, window weep holes, and elsewhere. On subsequent nights around dusk, we made a point of turning on our two roof vent fans (which have mesh screens), at low speed, blowing outwards, to suck outside air in through those same leaks. We hoped this would reduce any excess carbon dioxide at the leak points, making them uninteresting to the mosquitoes, and indeed it seemed to work quite well.

The next morning, after reaching the end of the RBJ at Km620, we stopped in Radisson to make reservations for a tour of the nearby hydroelectric facility. They said they could arrange a tour in English the following morning, so we headed for the last Cree village we would visit, Chisasibi (sheeSASibee), which was reached by paved road. There we enjoyed visiting the nicely arranged Chisasibi Heritage and Cultural Center. Past town, a gravel road went another 6 miles to the shore of James Bay, where we found Willow Ptarmigan and Rough-legged Hawk at the very southern edges of their breeding ranges, as well as a new sedge and a new willow. Returning toward the RBJ, we crossed over a dam to the north side of the La Grande River and drove out to Longue Pointe, seeing Beaver and Moose along the road. The end of the road, at James Bay, was the northernmost point we reached on the trip, just shy of 54 degrees latitude.

After camping out in a gravel pit on crown land, we returned to Radisson the next morning and took the very interesting tour of the Robert Bourassa Generating Facility, the world’s largest underground hydroelectric power plant. The facility is carved out of solid granite, and required removal of 83 million cubic feet of rock. The station is situated underground to allow water from the reservoir to fall 450 feet before striking the turbines, the energy of the water being proportional to the drop. There are 16 turbines, each producing about 350 megawatts of power. Because some of the original turbines have been damaged by cavitation, since being installed around 1980, they are being replaced at a rate of one per year, during summer, when electrical demand is lower (there being less air conditioning than electrical heating in Quebec). This provided an unusual opportunity to see the turbines and the structures housing them. The tour also including visiting the dam and the dramatic spillway, known as the Giant’s Staircase, which is about 400 feet wide, has ten steps each dropping 30 – 40 feet, and is about a mile long. The tour was fascinating, and free, and is highly recommended.

After a meal in town and topping off gas, we headed out the highly anticipated Trans-Taiga Road, built in the 1970s in support of hydroelectric development. This is considered the remotest road in North America, meaning that it ventures farther from the nearest town than any other roadway (460 miles!). Gas is only available at two private outfitters near the midpoint, and it’s a bad place to have a breakdown, as there are no repair facilities or parts available. We had high hopes of interesting mammals on this route, with even Wolverine being remotely possible, although the last confirmed record in eastern Canada was in 1978. On our way to a rustic campground at Km56, we had a good look at a cute Southern Red-backed Vole in the road. On our second day, we covered 90 miles, seeing Meadow Jumping Mouse, a life mammal for us; a black-phase Red Fox; and a probable Least Weasel. We paddled from our sub-rustic campsite at Km201 both after dinner and first thing in the morning.

When we arrived at Km286, we were devastated to learn that the outfitter had no gas. We did not have enough in our tank to try the only other outfitter at Km358, and there seemed to be no way to contact them to check; if they did not have any gas either, we would not be able to make it back to the closest gas on the RBJ. What a disappointment! We had planned on going to the Brisay hydroelectric facility, near the end of the road, and after which point the road quality is greatly degraded; instead, we had to turn back just halfway there. Other than a poor look at a possible Southern Bog Lemming, there was nothing of note on the return trip, which we broke up by camping again at Km56, where we finally saw Black Bear. When we ultimately did get gas on the RBJ, at the airport at Km589, the truck display indicated that we had only 5 miles remaining before running out of fuel!

We headed back down the RBJ, camping at Km440 (where we saw and heard a lovely Short-eared Owl at dusk) and our favorite, Km323. To finish our tour of the James Bay region, we took the Route du Nord towards Chibougamau. This is another long (250 miles) gravel road with minimal facilities (none in the last 180 miles). We camped in a rustic campsite at Lac Boisrobert, and paddled on the lake, seeing Black Scoter in its rather small breeding range in eastern Canada. This species also breeds in Alaska and adjacent Canada, but the two breeding areas are separated by about 1600 miles, a remarkable disjunction. The next night we camped on crown land with a beautiful view of a lake, and with Moose and Wolf tracks visible nearby. The first two-thirds of the road were quite scenic and enjoyable, but the last third was not because of a steady stream of logging trucks and other large vehicles kicking up clouds of dust that often did not clear before the next vehicle encountered. Mammals seen on the Route du Nord were Beaver, Red Squirrel, and Eastern Chipmunk.

And so our adventure ended. Mammals were in shorter supply than we hoped, but there was lots of quiet camping and nice paddling. A trip slightly later in the season would have been better for seeing migrant shorebirds and waterfowl, and there would have been fewer insects with which to contend. Overall, though, we were pleased to have seen new country and filled in an enticing section of the map with interesting experiences.